|

|

Coal

Power Plant Cleans Up Its Act

RAMFORD REGISTER

3/17/02

By Edison R. Menlow

CASTLETON, Ramford County. - A few miles west of Byers Point on the

shores of the Ramford River, in an area called Castleton, the land looks deserted.

Turtles snap their jaws at small insects along the bank; a hawk circles overhead; and cows

lay low in nearby fields. It's an unlikely place for a revolution, but

on the edge of this wetland habitat IECG is close to making clean-coal technology a reality.

The 1870-megawatt Castleton plant isn't much to look at. It hides its

power well. Providing electricity for about 50,000 nearby homes and most

of Ramford's industrial base, it has the feel of a giant erector set: all twisting pipes and rough welds.

But what goes on here - a process in which coal is cooked and turned into a

gas instead of burned to create steam - could change the future of coal power generation as we know it.

"Clean-coal technology doesn't need to be an oxymoron," says Art

Clinker, an engineer at CRPF (Castleton on Ramford Power Facility), one of

only a handful of plants in the USA making gasification viable.

"When this plant was built in the

'50s, it was coal fired. Later we went to oil, and then back to coal as

oil prices rose. We've kept up with the technology in keeping our

environment clean. We have always worked to be a good neighbor to the

river.

Folks have complained for years about

the smoke from our stacks, now they have nothing more to complain

about."

Referencing the entire plant in one sweep of his arm, Clinker continued,

"By the time we're done here, we'll have uses for just about all the byproducts; we'll be efficient; and we'll offer an environmentally safe

alternative to natural gas."

Whether that's actually possible is open to debate. In the late 1970s, utility companies began switching from coal to

oil and natural gas, which were

plentiful, more efficient and environmentally benign. When the price of oil shot up to $10 per million Btu from $2.50 at the time of the

conversion to oil, this utility company started looking for alternatives. Coal, plentiful and relatively

inexpensive, suddenly found itself at the head of the energy table.

There are certain truths about coal. Today it accounts for more than 50% of

the power generation in the USA. But because it spews toxins, coal has been

long viewed as the scourge of the power industry. America's traditional

coal-powered plants pump 2.3 billion tons of carbon dioxide into the air

each year - twice the amount cars produce. In 1999, the latest year for which figures are available, coal-fired utilities filled the air with 18

million tons of sulfur dioxide and nitrogen oxide, two major components of

acid rain.

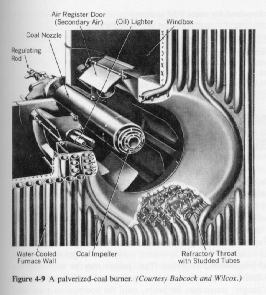

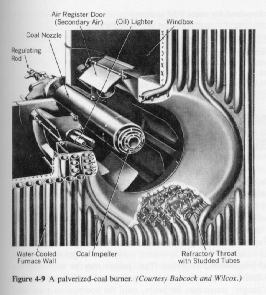

At traditional coal-fired utilities, huge iron-encased turbines pulverize

coal dust and pump it into a burner at tremendous pressure. The coal then

heats water and produces steam that spins a turbine. That, in turn, produces

electricity. That burning of coal is not only inefficient, but it is also

dirty and adds to greenhouse emissions.

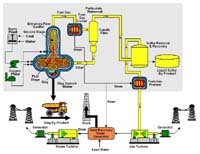

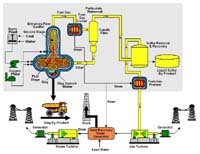

CRPF's gasification process turns coal into a gas and strips out the impurities before the emissions go into the atmosphere.

"See that," Clinker says, pointing to the seeming nothingness pouring out of

CRPF's three stacks. "Someone can be sitting near a coal gasification plant and see

nothing coming out of it. That's the goal." (In actuality, the clouds pouring from traditional plants are water vapor. It's the invisible gases,

like sulfur dioxide and carbon dioxide, that are greenhouse gases.

Clinker

admitted that carbon dioxide was spewing from the CRPF stacks, but you couldn't see it.)

Even so, compared with a typical coal-fired plant with modern pollution control devices,

CRPF produces 85% less nitrogen oxide and 32% less sulfur dioxide, according to

International Electric, the plant's corporate parent. Environmentalists are quick to point

out that's still 20-times more nitrogen oxide than a natural gas fired plant

and 100 times more sulfur. Natural gas emits virtually no sulfur.

Environmentalists say clean-coal technology is too little, too late. "This

is all well and good, but they should have done this when they converted

back to coal," says Gray Ashford, energy specialist at the Planet Resources Institute, a

Washington, DC-based think tank. "Federal money would be better spent on renewable energies," he says.

Sir Kurt Breaker (formerly of the UK and past Energy Minister for

Lancastershire Uplands, and now energy specialist at the Global Resources Defense Council,

agrees. "The concern isn't so much whether clean-coal technology works, the

big question now is whether they are robbing a variety of other technologies

to make clean coal viable."

CRPF is building on research that began in the 1980s, when coal plants were

shown to contribute to acid rain. In 1990, Congress amended the Clean Air

Act, phasing in tighter limits on emissions of soot particles, nitrogen oxides and sulfur dioxide. To help utilities come in under the more

stringent rules, the Department of Energy spent $1.8 billion on clean-coal

tech programs. CRPF is one of them.

Recently, most research has zeroed in on the development of super-efficient

burning methods so that plants can extract more electricity from less coal.

The average pound of coal contains about 10,000 Btu. Most coal-fired plants

capture about a third. Newer ones like the facility in Ramford County facility can extract

37%, and Ashford sees that rising to 40% within 10 years. The Energy Department has set an efficiency goal of 60% by 2025.

The gasification of coal requires a maze of chemical processes. The coal

first has to be ground up and mixed with water to create a slurry that is

the consistency of a good mud pie. A huge whirling drum with big teeth grinds down 2,000 tons of coal at

CRPF every day. Oxygen and the coal slurry are forced into a tall gasifer and they react about 2,400 degrees Fahrenheit

to form a synthetic gas.

Looking at Castleton on Ramford, it is easy to jump to the conclusion that clean-coal

technology may have actually arrived. But there is a catch. Construction

costs for conversion to gasification plants can be twice as much as those for standard

coal plants. The cost of producing energy is higher, too. The best gasification plants produce electricity for about $1,200 per kilowatt. Coal

pulverization plants produce at about $700 per kilowatt and natural gas,

about $1,000 per kilowatt. Ashford says the costs will come down over time, and the volatility of natural

gas prices makes gasification of coal a necessity for utilities hedging against higher prices. The challenge is convincing the power industry that

gasification plants are worth the expense.

The Bush administration may have a big say in whether that happens. A tiny

section of the Clean Air Act called the New Source Review prohibits power-plant operators from expanding old plants without installing

state-of-the-air pollution control devices. Utilities have said that the

Clinton administration's strict interpretation of the New Source provisions

stifled innovation and efficiency and are partly to blame for recent power

shortages. If the regulations are upheld, it could give utilities an incentive

to upgrade traditional plants with gasification facilities.

Gasification could also be an important part of the White House's new global

warming policy. After President Bush pulled back from the Kyoto Protocol to

combat carbon dioxide emissions, he ordered his Cabinet to draft an alternative that would appease European allies. Gasification could play a

big part in that plan.

Of all the energy sources, coal is the least expensive and most plentiful.

Worldwide use of coal for power generation is expected to double to 50% by

2015, according to Department of Energy figures. The Bush administration

proposed budget for fiscal 2002 sets aside $211 million for clean-coal programs - that's triple the amount from this year.

"You just need a little faith in the technology and in our ability to solve

these problems as they come up," says Clinker, surveying the plant. "Clean-coal technology is not only possible, we're

doing it."

|